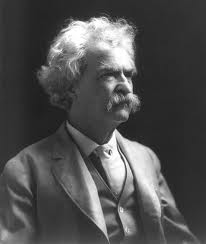

"Out of the Public School Grows The Greatness of the Nation"; the 112th Anniversary of Mark Twain's Boxer Speech

The health of the American Public school system is under debate in many different arenas: political, financial, social, ideological, and now, technological. At the root of these debates is our collective recognition or understanding confirmed by the author Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens):

"We believe that out of the public school grows the greatness of a nation."

I have used this quote many times myself, but I had never researched the quotation's context until recently. This quote comes from an address given to the Public Education Association at a Meeting of the Berkeley Lyceum, New York, November 23, 1900. The speech was given the title, "I am a Boxer", and its brief 588 word composition means that Twain spoke onstage for all of six minutes, applause aside.

I have used this quote many times myself, but I had never researched the quotation's context until recently. This quote comes from an address given to the Public Education Association at a Meeting of the Berkeley Lyceum, New York, November 23, 1900. The speech was given the title, "I am a Boxer", and its brief 588 word composition means that Twain spoke onstage for all of six minutes, applause aside.

The historical background for the speech deals with European colonization in Africa and Asia, and the American efforts to annex the Philippines. Predictably, there was resistance by the natives of a country resulting in serious and costly conflicts such as the Boer War in South Africa and the Boxer Rebellion in China. Twain had joined with a number of other Americans including William Jennings Bryan, Andrew Carnegie, John Dewey, and William James in an effort to stop a new rush to colonize. They formed the Anti-Imperialist League, and for a short time they coordinated efforts to stop the developing American Empire. Twain's speech also referenced Russia's involvement in the Boxer Rebellion in joint operations with US Marines and British troops.

On that Friday, Twain opened the speech to the Public Education Association with his familiar self-deprecating humor:

“I don't suppose that I am called here as an expert on education, for that would show a lack of foresight on your part and a deliberate intention to remind me of my shortcomings.”

He explains that his extensive travels had improved his understanding of other cultures, and that may be a primary reason for the invitation to have him speak. His best seller The Innocents Abroad had been published the previous year (1899), and he was lecturing extensively on this travelogue. But he also considered his audience and noted another reason for this address:

“The other reason that I can see is that you have called me to show by way of contrast what education can accomplish if administered in the right sort of doses.”

His argument against Anti-Imperialism was satirically addressed in the next two paragraphs suggesting if the Public Education Association's pictures that had been sent to an exhibition in Paris could convince Russia and France to withdraw troops from colonial conflict-how quickly world peace could be achieved!

He then illustrated his Anti-Imperialistic philosophy using the Boxer Rebellion by opening with a rhetorical question:

“Why should not China be free from the foreigners, who are only making trouble on her soil? If they would only all go home, what a pleasant place China would be for the Chinese! We do not allow Chinamen to come here, and I say in all seriousness that it would be a graceful thing to let China decide who shall go there.”

The last sentences in this section of the speech are the source for the title of this speech, "The Boxer believes in driving us out of his country. I am a Boxer too, for I believe in driving him out of our country."

The anti-immigrant declaration of "I believe in driving him out of our country" is surprising coming from the liberal Twain. One hopes he was playing to the sentiments of his audience rather than some xenophobic desire to keep America free of the Chinese. The Boxers's fierce opposition to Christianity did not make them popular in the United States. However, the statement could also be read as a converse to the statement that the Boxer is "driving us out of his country", a form of quid pro quo.

So how does Twain get from the Boxer Rebellion to public schools? In the paragraph that follows the declaration of commonality with the Boxer, Twain updates his satirical comments to note that, sadly, Russia would not be withdrawing its troops; there would be no world peace. Russia could choose to have an army or public schools, and as it could not afford both, Russia had chosen the army. Twain decries the choice:

“This is a monstrous idea to us. We believe that out of the public school grows the greatness of a nation.”

In using the pronouns "us" and "we" Twain joins the service of the Public Education Association. As he committed himself to the cause of the Boxer, Twain commits himself to the cause of the educator. Immediately after this statement, Twain includes a paragraph so prescient, a reader might think it came out of a recent town hall meeting:

“It is curious to reflect how history repeats itself the world over. Why, I remember the same thing was done when I was a boy on the Mississippi River. There was a proposition in a township there to discontinue public schools because they were too expensive. An old farmer spoke up and said if they stopped the schools they would not save anything, because every time a school was closed a jail had to be built.”

Twain wryly commented on his own anecdote with a familiar "Twain-ism", commenting that the practice of not funding schools was "like feeding a dog on his own tail. He'll never get fat. I believe it is better to support schools than jails."

He ended the speech with an off-handed compliment to the Public Education Association:

“The work of your association is better and shows more wisdom than the Czar of Russia and all his people. This is not much of a compliment, but it's the best I've got in stock.”

Twain's short address connected two unlikely ideas: the Boxer Rebellion and the American public school system. The speech is humorous, highly political, and frighteningly prescient. The thesis of his argument is not found in the title, but is found in the concerns he has about the funding of public education in America and abroad. In summary, Twain believed that nations who choose to fund armies over education will not be great. Education is necessary for world peace.

Mark Twain may have claimed that "I am a Boxer" in this short address, but he communicated quite clearly "I am an Educator." Public education already had wonderful resources in the literature of Twain with The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. This speech solidly affirms his belief in the importance of our public education system. His contributions to the profession of education have not been matched since.

Views: 61

Comment

© 2025 Created by Ryan Goble.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of Making Curriculum Pop to add comments!

Join Making Curriculum Pop